How To Laugh at a Fascist

With his global appeal and toothbrush mustache, audiences also connected Charlie to another massive figure of the early twentieth century: Nazi Führer Adolf Hitler.

Welcome to Reading Movies, I’m your host, Paul Klein.

Movies surround us and animate our world. One current candidate for the President of the United States, for example, keeps making references to Jonathan Demme's 1991 thriller The Silence of the Lambs in his speeches. But while movies permeate popular culture, movies don't project true images of society but only a sense of reality. Movies refract, rather than reflect, our world and provide fleeting glimpses and mediated understanding.

Like movies, online discourse also pervades the popular. Social networks like Twitter aren't real life, but their refracted realities offer a lens by which we can make sense of where we are. And if you've had the (dis)pleasure of being online in the last week, you're probably aware that some kind of shift is afoot. Over on The Platformer, Casey Newton calls this our “shitpost election,” writing that this moment feels like one where we’ve so “resigned [ourselves] to the ubiquity of misinformation” that our only natural response is to shitpost.

The latest craze in shitposting, of course, has been a collective effort to label the current iteration of the Republican party as “weird.”

And, oddly enough, it works. One after another, right-wingers are absolutely flailing to respond in a way that seems, well, normal.

But why is "weird" working?

“A Distorting Mirror, The One for Good, the Other for Untold Evil.”

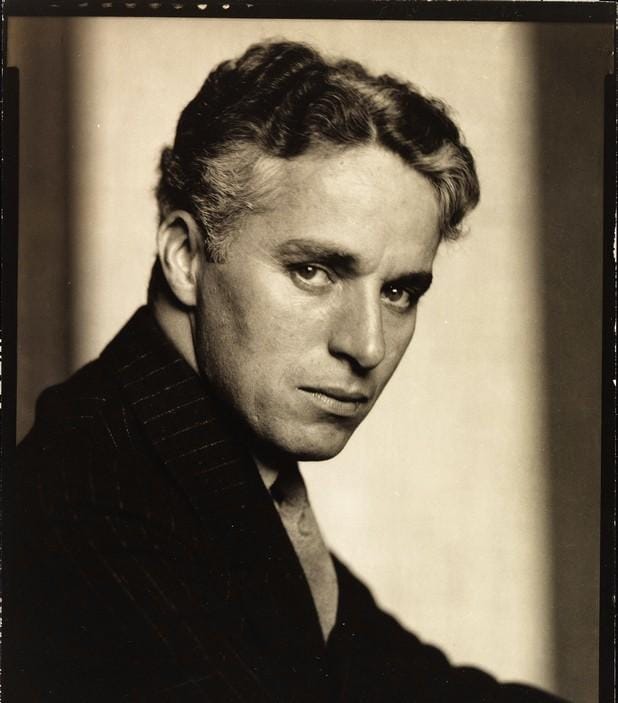

Another moment of right-wing authoritarianism offers an explanation. In the late 1930s, audiences across the globe already recognized Charlie Chaplin as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. In fact, Chaplin's star appeared so bright that many remembered the summer of 1918 as one of “Chaplinitis,” a worldwide phenomenon similar to Beatlemania or Taylor Swift's Eras Tour. Likening Charlie and his Little Tramp to a “mythical figure,” the French film theorist André Bazin later wrote that, “for hundreds of millions of people on this planet, [Charlie] is a hero like Ulysses or Roland.”

With his global appeal and toothbrush mustache, audiences also connected Charlie to another massive figure of the early twentieth century: Nazi Führer Adolf Hitler. In late April 1939, for example, The Spectator noted that both Chaplin and Hitler “mirrored the same reality—the predicament of the ‘little man’ in modern society.” Importantly, like cinema, the mirror in this analogy does not merely reflect. Instead, Chaplin and Hitler each became a “distorting mirror, the one for good, the other for untold evil.”

Chaplin's politics alternated between the staunchly apolitical and liberal. Following his expulsion from America in 1952, for example, Chaplin told reporters that, far from a political being, he was “an individualist” who believed above all “in liberty.”

Yet Chaplin's films largely exude liberal and progressive sympathies for the people that modernity and capitalism leave behind. “I didn’t have to read books to know that the theme of life is conflict and pain,” Chaplin wrote in his biography, first published in 1964. “Instinctively, all my clowning was based on this.”

No surprise, then, that, watching Hitler stoke the fires of hate from afar, Chaplin turned to comedy. “Oh, you bastard, you son-of-a-bitch, you swine. I know what's on your mind!” screenwriter Dan James recalled Chaplin yelling while viewing Nazi newsreels.

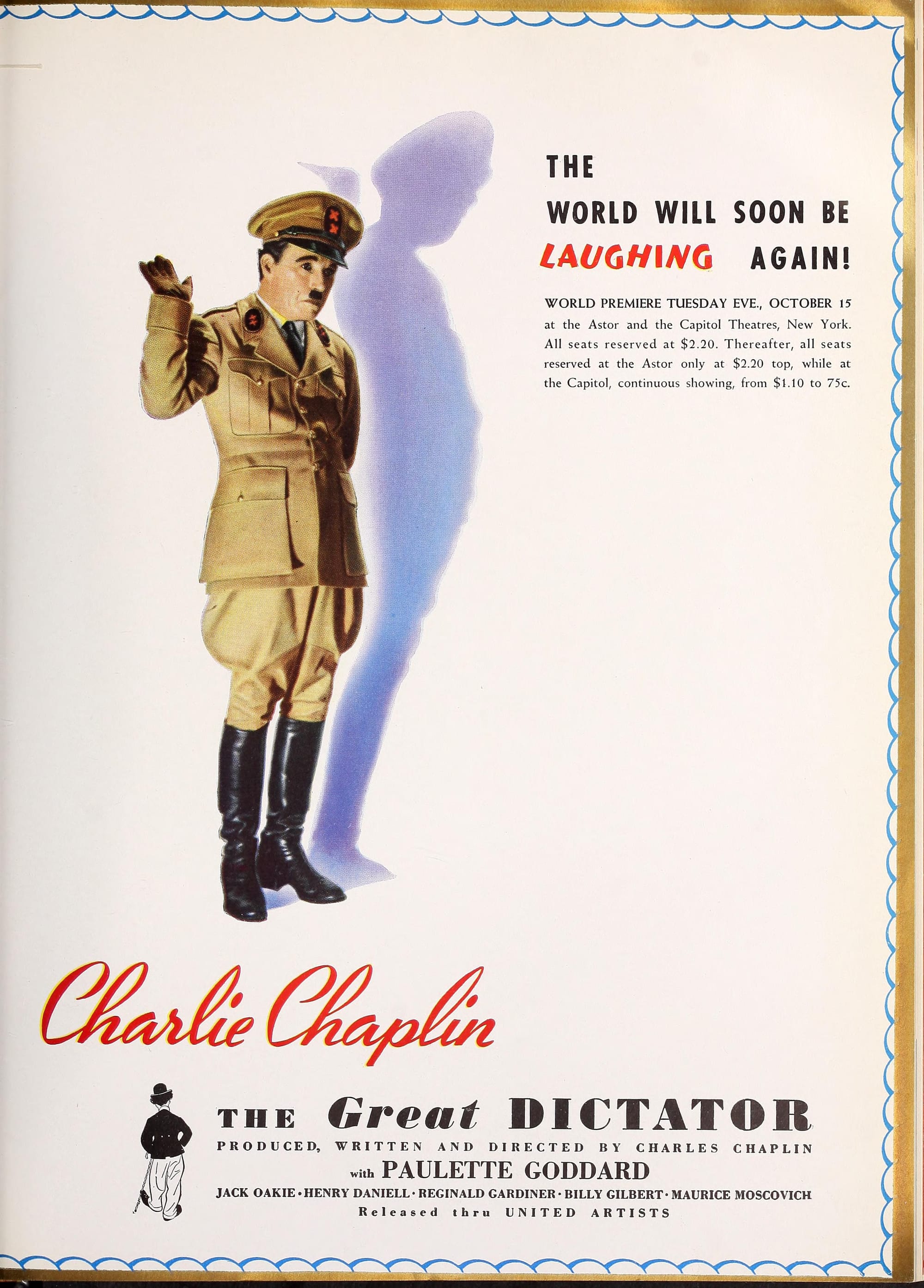

The result: 1940's antifascist comedy The Great Dictator. In the film, Chaplin takes on two roles. The first, a Jewish Barber who bears a striking resemblance to the second, authoritarian weirdo Adenoid Hynkel, the "Phooey" of the fictional European state of Tomania.

But how do you laugh at a fascist?

"If there's one thing I know it is that power can always be made ridiculous. The bigger that fellow gets, the harder my laughter will hit him."

Here, Chaplin demonstrates an expert understanding in the affordances of humor in the fight against fascism. “I thought Hitler was a humorless, horrible man,” Chaplin said. In part, it's this humorlessness that works “weird” under MAGA skin so well right now.

Launching comedic attacks bores through these bloviating buffoons because their politics actually center their own weaknesses and insecurities. Far from confident con men, fascists operate only on our fears. But however rightful these fears, turning our backs on those who abuse us deprives them of power.

“I’m sure there were moments when [Hitler] questioned his own genius,” Chaplin recalled. “You think of the power corrupting, at the same time defeating...I'm sure there's a false paradox there, where he was so effete and fearful of everything.” Chaplin understood how reclaiming power by exploiting fascist’s own fears works through comedy.

In one of The Great Dictator's most memorable scenes, Chaplin’s crazed dictator performs a solemn ballet with an illuminated globe. Pulling the piece from a heavy wooden stand—a direct reference to Hitler’s very own Columbus Globe for State and Industry Leaders—Hynkel cackles.

“I made The Great Dictator because I hate dictators,” screams the title of a Chaplin-penned piece for the September 24, 1940 issue of LOOK. “Hitler, to me,” Chaplin writes, “beneath that stern and foreboding appearance he gives in newsreels and news photos, actually is a small, mean and petty neurasthenic.” Laughing at fascists works because it strips them of their power over us.

In Kevin Brownlow and Michael Kloft's 2002 documentary The Tramp and the Dictator, Nikola Radosevic, a film worker in Belgrade during the Nazi occupation, recalls a moment of “cultural sabotage,” when he substituted in Chaplin's film during a screening for an assembly of Nazi paramilitary officers. “After 40 minutes, an SS man pulled out his gun and opened fire at the screen,” Radosevic recollects.

Our laughter enrages fascists because it reorients our fears and their supposed control in our favor.

The threats posed by authoritarians and demagogues are, of course, not laughing matters because they threaten our lives. But laughing offers one more tool in our arsenal against the fascist weirdos at our gates. The likes of Donald Trump and JD Vance are terrified that people will see them not as bullies, but as cowards. When we pop their balloon, we leave them holding nothing—no longer great, but little dictators, finally revealed as the pathetic, embarrassing weirdos that they are.

So keep laughing, and until next time, I’ll see you at the movies!

PT

The Great Dictator is available to rent or purchase from your preferred vendor or at a library near you. The Tramp and the Dictator is available as a special feature on the Criterion release of The Great Dictator, and can also be streamed on The Criterion Channel.

🤔 What do you think? Join the conversation on Bluesky or Letterboxd, or send me an email at paul@howtoreadmovies.com!

🎞️ Did you miss my Beginner's Guide to Classic Cinema? Read some of my tips and tricks for making the most of the the backlog, and see which films made the syllabus for PT's Classic Movies 101.